How to rewire our brains to beat climate change

We’re now feeling the effects of climate change, so why aren’t we doing more?

Climate change and exponential danger

How would you feel if someone said you’re short-sighted and easily led by others? That you also surround yourself with people who confirm your existing beliefs, and that you close your mind to new evidence that could prove you wrong?

It would feel awful, right?

Unfortunately, this describes all of us when it comes to risks that grow ‘exponentially’, because everything seems OK - until it’s not. And climate change is the poster child of exponential threats.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. After discussing the issue with Professor Paul Slovic (a global leader in decision research) and Oscar-winning Australian film producer Emile Sherman, we can now look at this once intractable challenge with renewed hope and confidence.

What makes climate change exponential?

There are several exponential drivers that play out in the climate change threat.

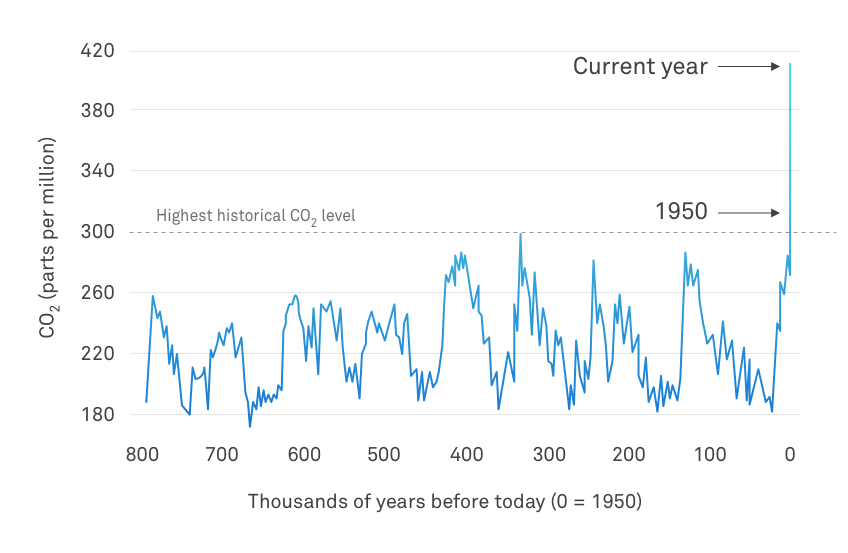

The graph below shows that the rate of increase in the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases (GHG) has significantly increased when viewed against the pattern of change prior to the 19th-century. In the last 171 years, human activities have raised atmospheric concentrations of CO2 by 47%.

Source: NASA global climate change - vital signs of the planet NASA global climate change

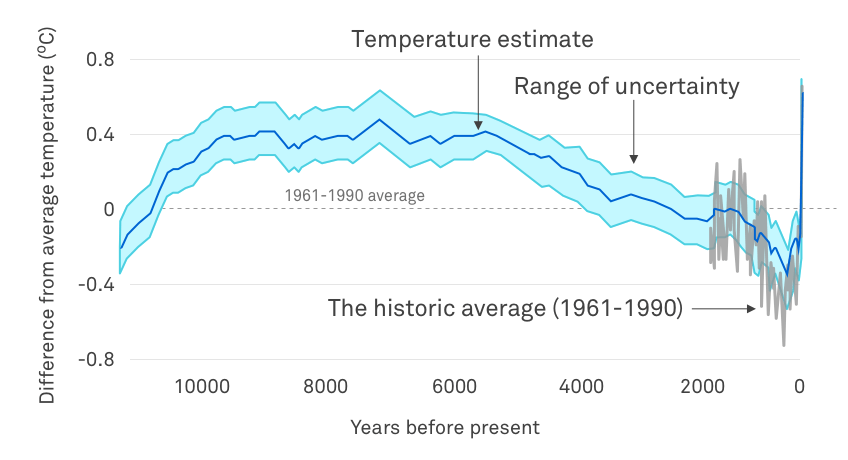

The next graph shows that, while the rate of change in global temperatures over the same period closely tracks the increases in the first graph, the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events has grown exponentially.

Over the past century, global average temperatures have risen from near the coldest to the warmest levels in the past 11,300 years, compared to historic average (1961-1990). The purple line shows the annual anomaly, and the light blue band shows the statistical uncertainty (one standard deviation). The grey line shows temperature from a separate analysis spanning the past 1,500 years.

Source: Climate.gov - Science and information for a climate-smart nation.

As the earth’s surface temperature increases, there are several tipping points at risk of being triggered, accelerating warming even further. Chief among these is the release of methane (28-36 times more potent than CO2 in terms of warming impact) from the thawing of Arctic permafrost.

The net effect of all of this? Everything seems ok until it’s not.

Why we close our eyes, and hearts, to climate change risks

What is real and what we feel are not the same thing.

Here’s Paul Slovic:

Our feelings serve as an important cue for our assessment of risks. Our feelings of risk are influenced more by our personal experience, and less by the facts. We don’t get emotional because we think something is a serious threat. We think something is a serious threat if we get emotional.

The ‘biases’ we all experience affect the way we think about – and take action in response to – the climate-change threat. In this article, we explore a few of these biases to give you a sense of the challenge, and to arm you with some fancy new terms when the conversation at your next barbecue turns to climate change.

Availability bias means we perceive more risk when a threat is memorable and feels close to home. We are simply not wired to experience emotional reactions (necessary to motivate action) in response to the statistical projections of atmospheric CO2 concentrations, average global temperatures, or even sea-level rise.

Here’s Slovic again:

"Climate change is exactly the kind of threat to which we become psychologically numb. The statistics of mass tragedies are like human beings with the tears dried off."

While Sherman sees this numbness as a barrier to constructing the kind of narrative to which we are wired to respond:

First, there’s no one villain, no one mastermind who has conspired to destroy the world. [Climate Change] is, instead, the result of many collective actions, resulting from a notion of progress that hasn’t been aware of its blind spots. Second, even if you identified the villains as being the policy makers of today, the result of their villainy is only felt well into the future. This lack of immediacy is tricky in narrative terms. Turning then to the victims, we find that, paradoxically, there are too many victims to empathise with. The number of humans affected means we lose the power of the singular.

People’s indifference over climate change has often been explained as a result of them knowing too little science to understand the evidence or not trusting the scientists. Yet research 3 conducted by Slovic with Dan Kahan et al. finds that many people who are more science-literate, are less concerned about climate change.

"How much each of us is concerned about climate change depends more heavily on our world view", says Slovic.

Specifically, people who tend to value individual freedom and the achievement of influence through climbing up the ladder of social rankings, and who resist collective interference with decisions (especially those relating to commerce and industry) tend to be sceptical of environmental risks.

This also fuels the ‘economy versus climate’ concept, due to worries that widespread concerns about environmental risk can restrict commerce and industry. In contrast, people with a more egalitarian worldview, who also value social justice, tend to be morally suspicious of commerce and industry (which is viewed as a cause of social inequity).

Unfortunately, those with vested interests can reinforce these world-view biases, and take advantage of our tendency for herding.

As Upton Sinclair famously noted, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it”. 4

As revealed in the work of London-based InfluenceMap, companies in the business of fossil fuel extraction have actively sought to (behind closed doors) shape public policy in ways that have held back action on climate change, often in stark contrast to their “official public positions”. As was the experience with the tobacco industry in the 20th century, the distortion of public opinion can take decades to unwind.

Says Slovic:

Differences in opinion on climate arise from a deep-seated conflict. On one hand we have a social drive to form close links with individuals who share similar beliefs about how the world works, and to distance ourselves from others who don’t share these beliefs. On the other hand, we all share an interest in making use of the best available science to drive improved environmental and economic outcomes by tackling climate change. Unfortunately, in America we became more divided along these lines in the last few years.

Slovic sees this in the way the United States reacted during the COVID-19 pandemic: "America is becoming more politicised generally, and COVID-19 was no exception. Wearing a mask became a political symbol, and to not wear one became a badge of honour. As a result, we have some of the worst infection outcomes globally.”

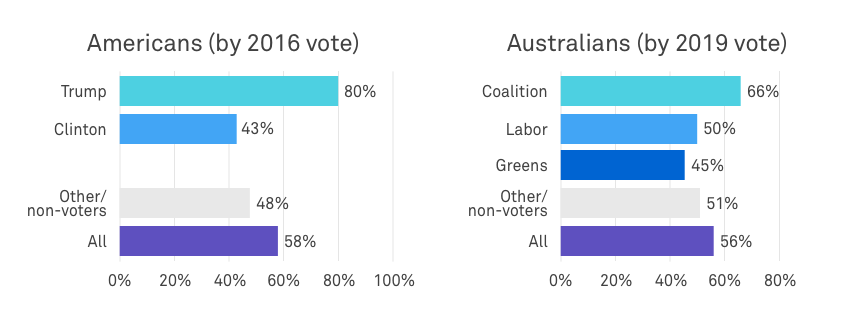

The good news is that this divide in Australia appears to be much narrower. As part of a survey by The United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, respondents in America and Australia were asked: "Do you agree or disagree that hard work and ability determine how well off a person becomes in your country?", which serves as a rough approximation for the "individualistic v egalitarian classification" explored by Kahan and Slovic.

The bar charts shows the results of the survey by The United States Studies Centre. In 2016’s chart, 80% of Trump voters believed that “hard work and ability” determines a person’s wealth, while only 43% of Clinton voters thought the same. In 2019's chart for Australia, we see that 66% of Coalition voters, 50% of Labor voters and 45% of Green voters felt that “hard work and ability” determines a person's wealth. This is a much narrower gap between voter groups in Australia, compared to voters groups in the US.

If the threat of climate change is known, why don’t we act?

Myopia and inertia bias mean that we are more reluctant to give up current comforts and conveniences, and downplay the severity of consequences that are likely to occur in the future. Our inaction on climate has long been reinforced by this idea of ‘the economy versus the environment’; that acting would involve significant economic cost (loss of comfort) in the short term.

Wanting to protect our hip pocket, confirmation bias means that we have paid more attention to evidence that enables us to defend our decision not to make change. This is amplified by the algorithms of modern media, which actively curate news and information for our consumption based on what we are most likely to digest (and share), rather than according to whether the content is credible.

Cognitive dissonance results in high levels of discomfort when we encounter actions or ideas that we cannot reconcile with our existing beliefs. None of us like being “proven wrong”. To address the discomfort, we find ways to dismiss new evidence that would otherwise change our beliefs.

Pseudoinefficacy means that we’re less likely to help one person when we’re made aware of the broader scope of people in need that we are not helping. With its effects played out through complex global mechanisms, and the victims dispersed throughout the world, it is easy to see how pseudoinefficacy affects our actions on climate change. Even heads of State succumb to pseudoinefficacy, declaring that emissions reductions in their own country would have a negligible effect compared to the emissions profile of (say) China. As Slovic puts it, ‘It’s like our own Government has given all of us a leave pass to not take action, which can be incredibly demotivating, and reinforcing this fear that “my actions” as an individual could be nothing more than “a drop in the bucket”.’

China’s announcement in September 2020 to become net zero is significant in this regard. Having the weight of an organised economy with over a billion people behind a net-zero objective weakens the “but China” excuse.

A strong case for hope in the fight against climate change

Emerging from the 2019/20 bushfire season we are finding that more individuals, families, communities and companies are taking action to address climate change. What was once a problem happening to “someone else, somewhere else, in some other time” became more personal. Suddenly, we were all immersed in a two-pack-a-day smoke haze from which there was no escape. As our article on Telstra reducing its emissions discusses, the future had arrived at our doorstep, and negative feelings about climate change exploded.

The weight of economic research and flow of investment capital is also dismantling the persistent view that “acting on climate change damages the economy”. As an example, modelling from Deloitte Access Economics indicates that acting to avert climate change will create more economic value than allowing the more extreme impact of climate change to occur. Sharing this message can dilute our cognitive dissonance (reluctance to give up economic value) and myopia.

In what was a tough year on many levels, 2020 showed us that herding can be a force for good. Think about how jarring it felt when we first started social distancing during COVID-19. Yet it quickly became an automated behaviour, when the crowd (the “herd”) adopted this new ritual in numbers.

Seeing our family, neighbours and friends make visible changes to their way of life to protect the community from COVID-19 appears to have changed our broader thinking about behavioural change. Research we conducted in 2020 revealed that 65% of Australians now agree the behavioural changes associated with COVID-19 have given them confidence in their abilities to make the shifts needed to address climate change.5

Here's Slovic again:

2020 represents a real chance to capitalise on availability bias. People’s receptiveness to change is most pronounced when the threat is visible and close to home. The bushfires and COVID-19 are both strong catalysts for behaviour change. Don’t underestimate the need for vivid scenarios with strong visual elements. We need stories that touch us emotionally, and reveal the reality of the future we are creating for ourselves.

Sherman emphasises that there are always "ways to construct effective narratives that ground our empathy and heighten the drama". To prevent feelings of pseudoinefficacy, his film LION focused on one of literally tens of thousands of Indian children who get lost at railway stations each year.

Sherman continues:

If LION was a film about thousands of children we would have cared less. [But because its focus centred around the challenges faced by the chief protagonist - the lost child – the audience could relate more, and as a result they became emotionally involved]. Interestingly, I’m now seeing many stories on climate change anchor themselves to the individual using the same 'one-to-stand-for-the-many' technique.

The tradition of post-apocalyptic films that can paint a vivid picture of our worst-case scenarios [also] has a role to play here, because narratives thrive when the stakes are high. But even in that context the power comes from the small stories, to find drama in unexpected places, and to play out the micro-narratives around policy that have ended up with macro-consequences.

Sherman is also seeing stories that "turn the environment into a protagonist-of-sorts, to feel the primal connectedness to our lived and shared spaces. It’s not easy, but it can be done."

Encouraging customers to make the right climate-change choices

Says Slovic:

"Our preferences can be changed by the way the choice is framed". "What we say is important, and what is revealed to be important through our actions, are two different things. Choice is not about belief; it is about what is defensible to us and to others. This can be harnessed for good".

Slovic’s advice to companies is basically to "make it easy for customers to make climate positive choices, and make it harder for them to defend choices that are bad for the climate":

- Help customers understand that they are making a difference. Remind them that they aren’t alone; they have joined a growing critical mass of others doing the same thing. Frame it in terms that matter. For example, "You are now one of X million Australian households who are …" or "If X million people do this, it will …"

- Remove any impediments to customers making climate positive choices. As an example, don’t make your net-zero products an option (and especially don’t charge for it) – make them mandatory.

- Without patronising people, reinforce the aspects of customers’ choices that speak to “who they are” rather than "the deal they got".

- Without speaking on their behalf, be vocal on the factors that have influenced your customers’ climate-positive choices, especially if they feel like their own voice is not being heard.

- Don’t sit on the fence, because sitting on the fence in this debate is to take the side of inaction.

How do we capture hearts and minds long enough to reframe choices? Sherman’s advice is simple: "Bring audiences into the driver’s seat of this drama, one that we know is more than just 'based on a true story'"

Let’s grab the wheel and get the narrative back on the track so we can live to see the sequel.

Footnotes

1 https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/.

2 https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/7/327/2016/esd-7-327-2016.pdf. https://news.ucar.edu/19559/searing-heat-waves-detailed-study-future-climate.

3 Kahan, Peters, Wittlin, Slovic, Ouellette, Braman and Mandel, “The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks” (2012), Nature Climate Change.

4 Sinclair, Upton (1994). “I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked.” Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-520-08197-0.

5 Research conducted by Blisspoint research in May 2020 on behalf of Belong.

Other articles you might like

sustainability

climate